I enjoyed reading E.C. Osondu’s book of fiction, This House is Not for Sale. The book shares many of the same issues that frustrated me in Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen (reviewed here) and Jola Naibi’s Terra Cotta Beauty (reviewed here) but still it does a great job of educating and entertaining the reader with humorous tales laced with historical accounts of a bygone era. The reader is regaled with witty observations from the eyes of a child living in a house (called “Family House”) filled with interesting characters, characters that could only have been conjured up by a mind on steroids. I recommend it to the reader dying for good fiction. The blog Africa is a Country has a good review of it here. Its opening paragraph aptly sums up the book’s portrayal of life in a Nigerian city where:

…everyday life serves as the stage for spectacular dramas and miraculous events, where every neighborhood has its fair share of characters and crazies—the white-garment church pastor, the dodgy police man, the mad man with his thing hanging out, the prostitute, the political thug, the old soldier, the witchdoctor, the quack pharmacist, the old lady who everyone thinks is a witch, the Phd holder without a job, and so on. Life with these archetypes existed in a continuum of the hilarious, the surreal, and the bat-shit crazy.

There are many things to like in the book – from the editing (which sometimes morphs into over-editing), to the meticulous research, to the disciplined, short sentences that showcase Osondu as a writer in charge of his craft. Osondu deploys an unusual but ultimately effective approach to writing this book that draws primarily on his strengths as a writer of short stories. There are eighteen chapters, each of which could stand alone as a short story, because each chapter seems to bear little or no relationship to any other. There are these fascinating characters, people with names like Gramophone, Baby, Cash, etc., each one assigned to a chapter. All through, Osondu maintains a disciplined focus on the character that owns the chapter to the near exclusion of others who remain in the shadows. It makes for easy and pleasurable reading.

Osondu toys with innovation in this book and he is successful at it. The mansion “Family House” that houses all these characters is a living, breathing, brooding character in its own right, ruled by Grandpa, the patriarch, mafia don, fixer and enforcer. It is a rowdy house, the reader gets the impression that it is a house of umpteen rooms. Many people come to this house in this mythical city to try their fortunes, seek solace from terror, flee their demons, and in a few cases, their crimes. “Family House” is a not-so-mute witness to life, dishing out opinions through its many characters that live in her. As an experiment in writing out of the box of orthodoxy, Osondu pulled that off nicely.

With this book, Osondu slyly turns the reader into Obierika, the wise one in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, who thinks about things and quietly questions the way things are. The book forces the reader to reflect on cultural norms with respect to relationships, patriarchy, misogyny, sexuality and sexual preferences, pedophilia (as in child brides) child abuse and labor, the new Christianity and its demons, the mentally disabled and their treatment, infertility, infanticide, corruption, etc. Again, these are familiar themes that run through most contemporary African fiction, except that Osondu does not preach at the reader. Indeed, it is the case that some of the characters, especially the children (Ibe and the nameless protagonist who narrates each chapter) try to fashion joy out of a war they found themselves in, and they mostly succeed.

This House is Not for Sale does not delve deep into any of the myriad issues it confronts, but like a good tweet, fills your mind’s mouth with rich imaginings. The book jogged my memory a lot and I grinned as I read of “sentimental songs” and revisited legends of my time like “Kill-We” Nwachukwu. Google him. Yes, Osondu has a phenomenal memory; his sense of recall is impressive.

For the Western audience, the abuses against women and children might seem savage and distant, of a time and a place where women and children could be expelled from their homes by men, sent packing to make room for a new bride. Except that corporal abuse, humiliation of women under flimsy pretexts (stripping them naked, beating them up and imposing corporal punishment on them) continue to this day in many of these societies, despite the slick and glossy noises of over-funded “empowerment” NGOs. But the book lets you think about those things without making any judgments.

The chapter named Ibe was my favorite chapter. Here, Osondu comes alive and one enjoys the power of his mind and his muscular writing skills. This chapter alone is worth the price of the book. The chapter took me back to my past and my childhood, to an era long gone, and I remembered a lot of things I had forgotten. Ibe, a cousin of the unnamed protagonist is an entertaining know-it all adventurous and impish boy who regales his audience with fantastic tales of his travels some of it made up in his head. My favorite lines are here:

Ibe paid for the movie with the money we got from the mission. Ibe bought suya. Ibe bought Fanta. Ibe bought Wall’s ice cream. Ibe bought FanYogo, Ibe bought Fan ice orange slush, Ibe bought guguru. Ibe bought epa. Ibe said we should walk into the movie theater like Harrison Ford walking into the Temple of Doom, we should walk in with a swagger and we should be swaying from side to side because no one could stop us. We did. (p 25)

I remembered this especially and I cackled with joy:

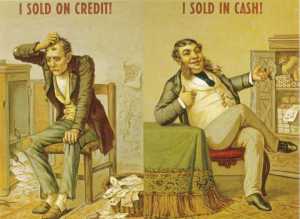

Cash had a framed picture in his store that showed two men. In one half of the picture, the man who sold in cash was smiling and looking prosperous in a green jacket and a fine waistcoat with a gold watch dangling from a chain and gold coins all around him. The other man who sold on credit was dressed in rags and looked haggard. All around him were the signs of his poverty; a rat nibbled at a piece of dry cheese in a corner of the store. (p 28)

Many of the stories are lovely but Ebi and Fuebi were my favorites. Fuebi was a good story, a bit more passionate and self-confident than the others, intense and filling. The chapter Currency reads eerily like a narrative of the recently concluded Nigerian elections. All through the stories, “Family House” is a constant presence, mute witness to living chaos, and enabler of dysfunctions, with Grandpa as the patriarch. In a sense perhaps, “Family House” is the main protagonist, the one that takes all our stories – and tells them – like the Internet. Welcome, new world.

Many of the stories are lovely but Ebi and Fuebi were my favorites. Fuebi was a good story, a bit more passionate and self-confident than the others, intense and filling. The chapter Currency reads eerily like a narrative of the recently concluded Nigerian elections. All through the stories, “Family House” is a constant presence, mute witness to living chaos, and enabler of dysfunctions, with Grandpa as the patriarch. In a sense perhaps, “Family House” is the main protagonist, the one that takes all our stories – and tells them – like the Internet. Welcome, new world.

Many readers might find the disconnectedness among the stories to be disconcerting especially as the book seems to be marketed, not as a book of short stories, but as a novel. I actually liked that the stories were loosely or not connected. Osondu tried to experiment with all these characters in this huge house and create stories that sometimes went nowhere. Just like life. He did not attempt a contrived plot; I think that took supreme literary confidence or chutzpah. Osondu did try to bring together all the stories in the last two chapters; that, in my opinion, was a messy mistake.

This House is not For Sale is not a perfect book; it reminded me of some of my pet peeves when it comes to African writing. It is written for a broad Western audience in mind; Many times, Nigerian words and idioms are italicized and carefully explained in the same or preceding sentence. African writers should perhaps learn to be more insular, I mean who italicizes akara and explains it as “bean cake” in the 21st century? If the reader is too lazy to use Google, tough luck. But then, to be fair, after all these years of railing at African writers, I now realize that African writers who choose to publish in the West are not negotiating from a position of strength; the editor is Western, the publishing company is Western and the audience is Western. It makes marketing sense. It doesn’t make it any less maddening. Imagine if Tolstoy in War and Peace had taken the time to italicize and explain every word foreign to the African reader. That book would have been way more than 50,000 pages. But then to be fair Nigeria has precious few indigenous publishing houses, what is a writer to do? You want to be published? Take the crap from the Western paymasters.

The chapter, How the house came to be uses conventional (and helpful) quotation marks to delineate dialogue; the others  dispense with it, which is confusing sometimes, especially when it is a long dialogue. Also, sometimes I felt like I was being read to as if I was a child. It is as if Osondu started out writing a children’s book, then he changed his mind. The tone of the prose may have been influenced by the fact that the protagonist is a child. The characters are mostly caricatures, many of them behaving like pretend-humans lolling about in an anti-intellectual society, lacking an ideological core and an abiding spirituality. That would be contemporary Nigeria. Perhaps this is the case, but between the 70’s and the 90’s, it boggles the mind that for many African writers like Osondu writing about that era there seems to be a dearth of serious minded people as characters. The African writer’s trademark superciliousness mars the book, somewhat.

dispense with it, which is confusing sometimes, especially when it is a long dialogue. Also, sometimes I felt like I was being read to as if I was a child. It is as if Osondu started out writing a children’s book, then he changed his mind. The tone of the prose may have been influenced by the fact that the protagonist is a child. The characters are mostly caricatures, many of them behaving like pretend-humans lolling about in an anti-intellectual society, lacking an ideological core and an abiding spirituality. That would be contemporary Nigeria. Perhaps this is the case, but between the 70’s and the 90’s, it boggles the mind that for many African writers like Osondu writing about that era there seems to be a dearth of serious minded people as characters. The African writer’s trademark superciliousness mars the book, somewhat.

In a few chapters, the over-editing by the editor lowered the boom and passion of Osondu’s powerful voice into a near-whimper. The attempt to sell the book to the West was relentless, and readers, young readers especially now used to the raw indigenous attitude of writing on the Internet and social media would look askance at parts of the writing. For Chinua Achebe, it was a simple trick; appropriate the English Language as if it were your own and tell your story. We need bold writing like that. Achebe’s editors amplified his voice, at least in his early works. Osondu needs a powerful editor who gets the power of his narrative and the need for the English Language to bend to the will of the story in a culturally sensitive manner. By the way, Aatish Taseer, writing in the New York Times (March 22, 2015) seems to speak to the frustrations of writing to, for, and through the West:

But around the time of my parents’ generation, a break began to occur. Middle-class parents started sending their children in ever greater numbers to convent and private schools, where they lost the deep bilingualism of their parents, and came away with English alone. The Indian languages never recovered. Growing up in Delhi in the 1980s, I spoke Hindi and Urdu, but had to self-consciously relearn them as an adult. Many of my background didn’t bother.

This meant that it was not really possible for writers like myself to pursue a serious career in an Indian language. We were forced instead to make a roundabout journey back to India. We could write about our country, but we always had to keep an eye out for what worked in the West. It is a shameful experience; it produces feelings of irrelevance and inauthenticity. V. S. Naipaul called it “the riddle of the two civilizations.” He felt it stood in the way of “identity and strength and intellectual growth.”

As a near-aside, just keeping the reader entertained with a book in the age of social media is an amazing feat in itself and Osondu passed that test with me. The reader is also facing personal challenges; social media is the new addiction that comes in short posts and grunts in tweets. Reading long form is now the new distraction. The intensity of feeling, the rush that comes with the instant feedback and contact with the reader and writer and the reader becoming a writer also (reader and writer exchanging roles). I don’t see myself as addicted to social media; many readers now see the book as a mere distraction from reading. Writers must provide leadership in confronting this threat against traditional scholarship and entertainment. Welcome to the 21st century. And oh, Osondu loves jollof rice. A lot. That meal of the gods is a recurring character in this peppy little book of many memories.