“But in another sense it was entirely appropriate to call Achebe a contemporary African writer, since African novel-writing has scarcely progressed since he inaugurated it with the celebrated Things Fall Apart. In the decades since that title was published—the same year as The Once and Future King, Our Man in Havana, and The Dharma Bums—the American novel has evolved through a multitude of vogues and phases while the Anglophone African novel has, for the most part, remained as it was when Achebe launched it: unremarkable in its prose, flat in its characterization, anti-Western in its politics, and preoccupied with the confrontation between tradition and modernity.”

– Helen Andrews (nee Rittelmeyer) in her essay Up from Colonialism, in the Claremont Review of Books, February 10, 2014

Perhaps, if I had to share my number one frustration about African literature, it is that its trajectory and fate are over-determined by the West. The conclusions get firmer even as the purveyors get lazier. Talking about labels, here is a New York Times interview of Teju Cole on the re-release of his debut book Every Day is for the Thief in which he tries to clarify his identity as a writer, and I guess, a human being. Specifically, Teju Cole demurs when referred to as an “African writer”, preferring the label, “internationalist” a la Salman Rushdie, whatever that means. I agree with him and respect his choice of identity. I am not sure the West cares; they are bent on making him and all writers of African descent, the exotic other. Because even though African writers protest too much, many of them have spent a lifetime making money and fame from hawking themselves as “the other.”

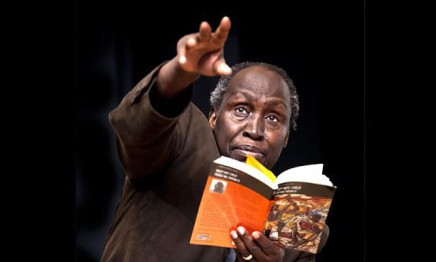

Let me also say that “African literature” in the 21st century, to the extent that it is only judged through analog books by literary “critics” schooled in the 20th century Achebean era, will always distort our history and stories. I have said that many African writers write poor fiction because they tend to force their anxieties about social conditions into the format of fiction. The result is often awkward, they should be writing essays. But I was primarily thinking about books. Today, the vast proportion of our stories is being written on the Internet by young folks who do not have the resources that the West availed Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o et al in the 60’s. Why are we judging African literature only through books? Why?

Let me also say that “African literature” in the 21st century, to the extent that it is only judged through analog books by literary “critics” schooled in the 20th century Achebean era, will always distort our history and stories. I have said that many African writers write poor fiction because they tend to force their anxieties about social conditions into the format of fiction. The result is often awkward, they should be writing essays. But I was primarily thinking about books. Today, the vast proportion of our stories is being written on the Internet by young folks who do not have the resources that the West availed Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o et al in the 60’s. Why are we judging African literature only through books? Why?

There may be some truth to the notion that many African writers who write fiction are yet to wean themselves of Achebe’s influence. But then, the critics who make these charges should look in the mirror – and then get off their lazy butts and go read new African writers. They are out there on the Internet and in literary magazines doing us proud. And how you can do a literary critique of contemporary African writing without once mentioning Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie beats me. What about Taiye Selasi? NoViolet Bulawayo? And we are still talking about books. Give me a break, people.

Lastly, to imply that Achebe was an ordinary writer is beneath contempt. Literature, stories must not be divorced from their context. Achebe’s generation wrote for my generation of children because no one else would. I would not be here today without them. They were preoccupied with the social conditions at the time, yes, but they tried to do something about them also. Indeed some died fighting for an ideal (Christopher Okigbo for instance). The challenge for today’s writers is to ensure that they are not merely recording and sometimes distorting and exaggerating Africa’s anxieties and dysfunctions for fame and fortune. To blame Achebe for our contemporary writers’ narcissism is disingenuous and silly.

Lastly, to imply that Achebe was an ordinary writer is beneath contempt. Literature, stories must not be divorced from their context. Achebe’s generation wrote for my generation of children because no one else would. I would not be here today without them. They were preoccupied with the social conditions at the time, yes, but they tried to do something about them also. Indeed some died fighting for an ideal (Christopher Okigbo for instance). The challenge for today’s writers is to ensure that they are not merely recording and sometimes distorting and exaggerating Africa’s anxieties and dysfunctions for fame and fortune. To blame Achebe for our contemporary writers’ narcissism is disingenuous and silly.