Yemisi, I have saved the best words for you. For you…

My son is the reason behind my forthcoming book Longthroat Memoirs. Even if I loved stories before he arrived, I had no strong motivation to collect them and examine them in the context of food. He woke me up at 5am to cook breakfast and kept me on my feet all day cooking. I angry, exhausted, depressed and raging against everything. The necessity of cooking day in day out produced two and a half years of writing for a Nigerian newspaper on food and a faltering blog on food. And it also produced Longthroat Memoirs.

– Yemisi Aribisala (November 7, 2015), in the essay, Mother Hunger

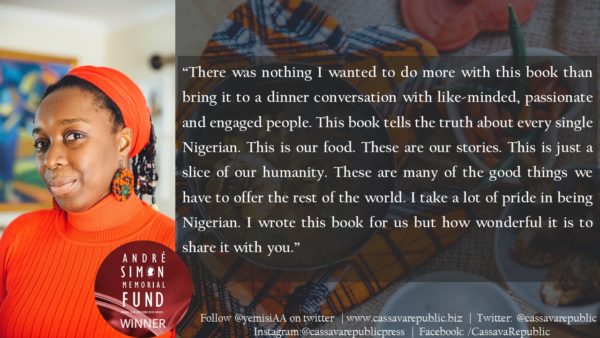

There are many reasons why you must read The Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds, Yemisi Aribisala’s lovely volume of essays, published by Cassava Republic Press. One: It is a gorgeous book, professionally done, one that proudly adorns my coffee table, Cassava Republic Press exceeded my lofty expectations on this one. Two: Aribisala dispenses with the pretense of narrative through fiction and tells her stories straight. Thus, unburdened with rules, the stories fly out of her fecund mind, lush rivers of thought feeding into the reader’s mind-road. In the process, with muscular essays, she joins thinkers like Chinua Achebe in rejecting the stereotype of the African writer as a mere storyteller, not a thinker. Three: She successfully injects respect into Nigerian cuisine with well-researched pioneer work and taunts the stereotype of Nigerian food as stodgy and unimaginative. Four. The Longthroat Memoirs introduces you to one of Africa’s finest essayists, an erudite thinker who has masterfully surfed the waves of the digital revolution to force feisty and important debates on a breathtaking range of subjects from feminism to the texture of moin-moin. Compared to worthy compatriots whose books are published in the West, she is relatively unknown. If you don’t write a book published in the West, you are invisible, you have no voice. This sad reality begs the question: Who speaks for Africa? The likes of Aribisala who write for Africans are hidden in plain sight in favor of those who italicize their egusi and twist their words and accents to fit foreign (Western) tastes.

Some of the most important debates on African issues have ensued online thanks to many of Aribisala’s powerful essays. She has, more than virtually any of our writers of stature influenced the trajectory of modern thought within the African literary/intellectual community. She will not be recognized this way, but be defined and limited by the one book she has published. The Longthroat Memoirs is an awesome book, no ifs, no buts about it, but it is only the gorgeous tip of the impressive work Aribisala has been putting out for many years online, starting with Farafina magazine. I have old copies of the now defunct Farafina Magazine, where she was founding editor, that show that Aribisala (Yemisi Ogbe at the time) was defiantly appropriating English as her own. As an example, in her epic essay, Giving it all away in English (Number 6, August 2006, reproduced by Chimurenga in 2015), she wonders impishly: “If we are progressive enough to understand that Jamaicans have made the English Language comfortably theirs in spite of colonization, why haven’t we successfully done the same in Nigeria without condemning those who speak with and accent or make grammatical mistakes to purgatory for the incompetents and erudite?” She was talking about the appropriation of English as an African language many years before it became the burden of a chic debate.

There are more compelling reasons to read The Longthroat Memoirs. Historically African writers have treated food and sex at best as a collective afterthought, but many times as taboo subjects. Reading through African fiction from Achebe to Adichie, one gets the definite sense that African characters rarely eat or have sex, and when they do there are enough apologies to fill the River Limpopo. The single-story narrative of poverty porn hawked by many African writers does not associate Africa with good food and great sex. To hear many of these writers say it, Africa is a land of stick figures, distressed disease-ridden pretend humans leading meaningless lives, stumbling from war to pestilence, gouging on empty air – or the occasional road kill. To be sure, there are delightful exceptions; one of my favorite passages in Wole Soyinka’s You Must Set Forth at Dawn describes a feast to die for in his bosom friend’s house. He tells the tale with much pride and one marvels at the fusion of friendship and repast.

The good news is that things are changing; a not-too silent revolution is happening among African writers, they are re-tooling the narrative to redefine writing from Africa and to include the sum total of the experiences of the continent’s citizens. In Longthroat Memoirs, Aribisala ups the ante with a cunning and stunning way of writing a memoir that connects the rich dots of humanity from her lived life, to the rest of us. And food (accompanied by notions of sexuality) is the common thread that connect the dots, from ekoki in Calabar to eccles in London. Aribisala talks about herself as if she is talking about food and by the end of this rich volume of essays, you can pretty much piece together much of her life’s journeys, to the extent that she lets you. You sigh in awe as she talks about her life with a near-clinical detachment and then you fall in love with this quietly defiant warrior who is determined to live life on her own terms, regardless. So what is this book about? Many reviewers have called it a book about Nigerian food. It is and it is not. It is like calling Achebe’s Things Fall Apart a book about a simple farmer and his yams. Perhaps we should return to Aribisala’s passion and say that she used food as a delicious basis to permit us a peep into our lives, anxieties and joys and to demonstrate that our varied experiences as human beings are like the many rivers that run through the earth; perhaps they end in the same place, who knows?

Aribisala’s book is a multi-dimensional tour-de-force; we learn about Nigerian regional cooking and cuisine, and we find out that despite its exotic ways and crude, if cute instruments of measurement (who measures ingredients with the precision of empty tins of tomato paste?) it is complex and is governed by rules of science, and art, spirituality, and in some cases superstition. You learn all of this with prose remarkable for its beauty and brilliance. Aribisala is the legendary journalist Peter Pan Enahoro with even more substance. And one remembers Achebe’s brilliant essays in the way she uses food as the palm oil that aids the digestion of life’s lessons. Achebe once stated that he wrote children’s books because the ones from the West were not written for his children. Decades from now scholars will marvel at Aribisala’s prodigy, this warrior who wrote about Nigerian cuisine and culture in a way that has never ever been done before. This is great stuff, As an aside, I can visualize Aribisala teaming up with the itinerant TV personality chef Anthony Michael Bourdain traipsing the great nations that make up Nigeria and tasting the various degrees of ogbono that are out there. Better yet, I would subscribe to an online portal dedicated to her mind. But I digress.

I digress. Back to the book. The Longthroat Memoirs is a hugely ambitious undertaking which serves to prove that Nigeria should be a continent. Yes, Nigeria is a large country and anyone who tries to capture all of Nigeria’s cuisine and its various shades and iterations will die of unresolved dreams. Hell, in my village, you can tell ogbono from clan to clan. You can taste the changing earth and seasons as ogbono, that sauce of the gods, roams from clan to clan. Starting with Calabar, Aribisala really concentrates on cooking from certain regions largely in the South, including mouth-watering forays into the riverine and Edo speaking regions of Nigeria’s old Midwest. Even at that it is an ambitious undertaking. As Aribisala finds out, Nigeria is a nation of hundreds of little nations. In the end, she triumphs as she wraps her hands and her head around that complex nation space called Nigeria. Writing with wry humor and intimidating brilliance, the reader learns of everything from meat substitutes to sex. She explores the mystery and myths of the ingredients of soup and sex in Nigeria. She struggles with the definition of Nigerian “soup” until she gives up triumphantly and declares that there is no comparison; there is soup and there is soup. When one calls ogbono soup, a lot gets lost in the translation. Here, soup is an indigenous Nigerian word, it is not English. It is certainly not sauce.

Aribisala’s passions, heart and soul are firmly rooted in the soil of Nigeria’s ancestral lands, and in soaring prose-poetry she lets her angst rip. Outside of Nigeria she is inconsolable. Here is a poignant definition of exile:

You just can’t buy local chicken in Brixton or Peckham High Street. Not the kind that tastes Nigerian. The plantains are a rip-off. They are not sweet. They are pretenders. The yams are tired and shrunken from travelling so far. There is no fresh afang to be bought, no fresh pumpkin leaf. The ogbono seeds are not first-rate; you can smell rejection on them. (pp 88-89)

Yes, The Longthroat Memoirs is about cooking, life, sex, patriarchy, misogyny, love, loving, ethnic and class distinctions, lust, longing, exile and the nostalgia for home; all those ingredients that go into making what passes for living in Nigeria and elsewhere. From Aribisala’s perspective. It’s all fascinating. And she pulls it off. There are forty-two essays in this volume, if you include the introduction, which is a full-blown essay and an excellent summary of what the book is about. Indeed, the introduction qualifies as a great self-review and enough excuse to buy the book. Scholars will have their hands full deconstructing all that is in these essays, each one is the proverbial dry meat that fills the mouth that will keep a class of inquisitive students entertained and educated.

Each essay deserves its own review. Indeed, this text should be required reading in online multidisciplinary courses at the tertiary level, it is too rich for just leisurely reading. You will fall in love with the essay My Mother, I will Not Eat Rice Today, a wildly hilarious and brilliant deconstruction of social conditions in Nigeria via a little boy’s culinary anxieties. Here, Nigeria comes alive and you do not need pictures to feel and taste the land. It is a great riff on Lagos. And Lagos comes alive, you can feel the breeze strolling across the lagoon. It features also a good recipe for jollof rice and some of Aribisala’s best prose. In Akara and Honey, the prose is so good you might as well be eating every letter of every word and be calling it akara. Sigh. Oh and Aribisala has a recipe for akara that she swears is the perfect therapy for PMS. How? Go and read it! Kings of Umani is a throaty rejection of the ubiquitous Maggi bouillon cube in favor of making stock from scratch.

Letter from Candahar Road is so poignant and funny, one remembers Soyinka narrating how he smuggled bush meat into the West and risking being the first Nobel Laureate to be arrested for poaching. Okro Soup, Georgeous Mucilage is about the many ways to cook okro, mucilaginous things and hints of sex and it also reminds the reader of a time when ships sailed to Nigeria bearing Shackleford Bread. It is about the pull of home and the purgatory that is Babylon. Longthroat Memoirs, the essay that bears the title of the book, is a lovely ode to the land, jazzy, laconic but still taut with longing. Aribisala recreates the streets of Ibadan with the dexterity of an orange seller peeling oranges with knives fashioned out of empty margarine tins. You must read The Snail Tree, a free-flowing discussion about everything from snails, to sex, to Wainaina Binyavanga with everything thrown in between. It starts out with quiet defiance and quiet force and ends in quiet defiance and quiet force:

I have saved the best words for you. For You. There are places in a woman that a penis will never reach. I have said it. And what I mean to say and don’t feel under any pressure to reiterate, but will say again anyway because I was asked for my opinion, is that sex is overrated. (p 111)

In Fainting at the Sight of an Egg, impish sentences troll the Nigerian condition with deadly accuracy. There are many uses for an egg, we find out, including as a test for virginity and you laugh like a maniac as she lampoons a fridge suffering epileptic power supply. In Sweet Stolen Waters, every sentence is a deliberate work of art communicating something – with flair and attitude. There are all these sentences writhing with energy, turgid from sexual suggestiveness. This book is horny. When Aribisala riffs on plantains, the reader’s loins stir with longing and wonder:

They are luscious and thick and the yellow colour of ripeness burns holes in the retinas. Frying them is sacrilegious; they must be steamed in their skins. When they are removed from their skins they look too good to eat, like beautiful golden rods. Their texture is soft, spreading slightly on the tongue. They’re sweet with hints of treacle, hot all the way into the depths of the stomach, every atom delicious in every ramification. (p 148)

Aribisala loves the land and her seas and she writes about them with such tenderness, it is sometimes heartbreaking. Ogbono is a goddess, and rightfully so, says the essay, A Beautiful Girl Named Ogbono. Only Aribisala can dredge up romantic notions about ogbono soup, who knew? This essay is the most comprehensive study of the effect of first rate palm oil on the quality of ogbono soup. It puts the researchers of Nigeria to shame, they should go burn their degrees. To Cook or Not to Cook reads like a well thought out feminist manifesto, immensely readable and one that one can relate to because it is grounded in the reality and context of life in the ancestral lands of Nigeria. Between Eba and Gari muses on bigotry, ethnic anxieties and the politics of food jokes. Ila Cocoa is pure delicious prose-poetry. Here the recipe is the story. Brilliant. In the prose-poetry of Fish, Soups and Love Potions, one remember the haunting beauty of Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country.

River Oyono is a smoke-grey cloak animated by a strong wind. It is, in fact, only a small conceited river. It embraces the Atlantic Ocean for a passionate 24 km. Just before the open seas, there is an unusual meeting point of brackish and fresh seawater, creating an environment that provides stunning produce for the markets in Calabar. They say you will find fish there that you will not find anywhere else in the world. (p 275)

Peppered Snails is a stifled climax, the closest Aribisala would allow the reader peek at a love story. Here, Aribisala, is the composite of all those women gathered around a tripod, cooking, laughing and singing songs of the oppressed. Bush cuisine is a delight as we encounter what the white man would call game or venison. Read The Market Place and remember Molara Wood’s enchanting short story, Night Market in Indigo, her book of short stories.

Aribisala probably hates labels but she is an Afropolitan, with eclectic tastes that range from Rex Lawson to Sergei Rachmaninoff. Still the sea draws her near with her mucilaginous tentacles. The trademark superciliousness of the African writer is there in full force. There is the obtuseness of Soyinka: When Aribisala says, “Local olfaction collapses the astringency of smoke into the idea of fresh air, as if that were possible,” one remembers Soyinka’s “Metal on concrete jars my drink lobes” and one chuckles, with great fondness for these weird ones. Yes, the book sometimes comes across as too rich, like too rich soup. Sometimes you feel like you are reading Teju Cole of the fine mind, with the refined senses, of writers of color who have traveled to all these places, eaten all these wondrous things while listening to music that comes out of rare and expensive pianos instead of from empty Fanta bottles. Burdened with a mind on steroids, she overthinks things. Sometimes one just wants to eat, shit and fuck. Why the drama? But then, that could be this reader’s problem, to be a philistine, a peasant autodidact should be a crime. Yes. Aribisala is aware of her wealth and she flaunts it. The book is an embarrassment of riches, it is not gaudy but everything is in this pot and you wonder what will happen when this pot is exhausted, will you eat again? The photographs are nice but they only made me hungry for more. Collaboration with photographers and graphic artists would have been an even nicer touch. I miss hot links to the various terms and recipes. A digital version is not available, which I find disappointing.

The Longthroat Memoirs is also a conversation about what gets lost in the translation when you express yourself in an alien language, as I have argued elsewhere and ad nauseam. What does the term “fattening room” really mean in Calabar? We may be relying too much on a colonial and racist interpretation and turned a once honored ceremony into a pejorative. Today, post colonialism, the kitchen is the most visible totem of subjugation. Did we have kitchens before the coming of the white man? It is a great question: In my village, there was more clarity in roles between men and women. The men were the hunters and gatherers and all the spoils came home to the women who managed spoils and the household. There was no word for “kitchen.” These days there is a perversion of culture and women and children are the victims. Aribisala sometimes trades in stereotypes, put-downs, and stick figures and after a dozen essays it begins to grate on the reader’s nerves:

The archetypal businessman in Calabar is the civil servant, married with three children, two house-helps, a complicated and dependent extended family, two cars and a racy mistress with a large bottom who owns a small boutique. He closes work at about 4 p.m., and with so much free time on his hands, he would be ungrateful not to carouse in it. He is a devout Presbyterian, goes to church on Sundays, makes love to his wife once a month, visits his mistress once a week and fills the rest of his schedule with slender UniCal girls who have stomachs like chopping boards and skin smooth as processed shea-butter.

The antiquarian fattening rooms where women are still sent to grow love handles and learn the intricacies of how to pamper men’s personalities into that of suckled babies might be on their way out, but that spirit of male entitlement to as many available women and young girls as are willing remains.

Women are indoctrinated from a young age into the mindset that men have all the advantages and, to be truly successful, a woman must somehow attach herself to a successful man, be it brother, husband, uncle, lover or sugar daddy. Enter that necessary artillery among artilleries: cooking. A woman must cook well; very, very well. Sex is a given, but it doesn’t have to be outstanding sex. Sometimes the man wants a docile lover, but there is no compromise when it comes to food. A man will not marry a woman who cannot cook (a true abomination), nor will he emotionally desert a wife who can cook to play with a mistress who can’t (a ridiculous proposition). A suitable wife must be a good cook, attractive, homely, God-fearing and must come with a guarantee that she will bear children. A shrewd mistress must be a great cook; flatter diabolically; keep a scented, relaxed, undemanding second home where foot massages are spontaneously administered; know how to at least pretend some degree of sexual kinkiness; and know how to engage a man for as long as possible by whatever means necessary. (pp 277-278)

The Longthroat Memoirs is a great compilation of a fraction of Aribisala’s essays, most of them from her days at the brainy but ultimately troubled NEXT newspapers where she ran a blog. There is the equivalent of several volumes of books of her works scattered all over the Internet. It is a sign of the times that the enterprising internet-savvy reader can find some of them online (for example, the luscious Fish soup as love potions as well as this excerpt in The Guardian). Chimurenga has a rich archive of her works here that shows the breath-taking range, vision and courage of Aribisala, from an insightful essay on the artist Victor Ehikhamenor, to a review of Adichie’s Americanah. Google searches will find her brilliance scattered all over the place like this essay on Nigeria and the culture of respect. There are good interviews of her (here, here and here) that provide rich insights into this quirky goddess of words. It is sadly ironic that The Longthroat Memoirs will probably be used to define Aribisala’s contributions to writing. That would be a huge disservice to her prodigy and industry, she is easily one of Africa’s most quietly influential thinkers.

This brings me to my pet peeve: The unintended effect of using the book as the sole yardstick of writing is to severely underestimate the worth of the African writer. When hard print was the main medium of literary expression (as in books), it was appropriate to use the book as the sole determinant of a writer’s output. In the 21st century, in the age of that infinite canvas called the Internet, this yardstick is a travesty and especially unjust to African writers who are increasingly turning to the Internet for relief from mediocre or non-existent publishing industries. Aribisala should be remembered in writing history as the total sum of her works as compiled (albeit haphazardly) on the Internet. When NEXT newspapers folded, the proprietor simply shut down the website and writers like Aribisala were left with nothing but drafts as evidence of work done over a period of several years. The Longthroat Memoirs, to the extent that it beautifully recreates those essays is perhaps the best evidence that at least as an archival tool, the death of the book is a tad exaggerated. Still, I dream of an online library where there will be entire digital books like The Longthroat Memoirs with hot links to explain stuff, with forums for debates on the several issues that Aribisala so coyly throws up. Readers would happily pay for the service. I will gladly pay. Yup, to be at the table listening to this eclectic, quirky thinker from Hades’ lascivious kitchen, cerebral dominatrix, talk about snails, mucilage and love in one breath, and on her own terms, coolly indifferent to your pressing needs, knowing that she will feed you and love you in time, on her own terms. Now, that is a book to die for. A reader can only dream.